Two centuries after the birth of the Brontës, an ongoing programme of events has been celebrating their pioneering lives and literature. However, a forthcoming conference (open to anyone) will put a different spin on the siblings by examining them in terms of “coarseness”. READ chatted with Sophie Franklin, one of the organisers of The Coarseness of the Brontës: A Reappraisal, to find out how this event on 10th-11th August will cast fresh light on the family.

Some people may be surprised to hear the Brontës described as coarse. Where did this theme for a conference originally come from?

Contemporary reviewer Elizabeth Rigby complained that “it is stamped with a coarseness of language and a laxity of tone which have certainly no excuses in [our time]. It is a very remarkable book: we have no remembrance of another combining such genuine power with such horrid taste.”

Elizabeth Gaskell’s, and even Charlotte Brontë’s, portrayals of Haworth as a social backwater of brutality and incivility have helped to embed the idea of “coarseness” into the family’s legacy, something which is difficult to shift. So, “coarseness” is at the heart of how the Brontës were perceived as writers in the mid-nineteenth century.

Is this still the view today?

Not necessarily. Often their novels, especially Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, are seen more as romances with Rochester and Heathcliff positioned as romantic heroes. Considering how violent both men can be in the books, this romanticisation is a little unsettling.

It was with this contradiction in mind that my co-organiser, Claire O’Callaghan, and I wanted to reappraise the so-called “coarse” aspects of the family’s lives and works, to ask why the Brontës may not be considered as “coarse” nowadays, and to consider whether the notion of “coarseness” has shifted over time.

We’re currently celebrating the bicentenary of Branwell Brontë’s birth. How does he relate to his more famous siblings in terms of “coarseness”?

Branwell Brontë is a really interesting figure, as he played an instrumental part in the development of the siblings’ juvenilia. He and Charlotte in particular were writing partners-in-crime for much of their childhood and adolescence. The stories they wrote based in their tempestuous imaginary realms – variously named Glass Town, Verdopolis, and Angria – acted as a writing workshop where they honed their literary skills and authorial voices. Branwell was also the first Brontë sibling to publish his own work in periodicals under the pseudonym, Northangerland, his nom de plume. Many remember him as a bit of a waster, which is unfair, not least because he most likely suffered from alcoholism and drug addiction, both illnesses that we now thankfully view with more compassion (although there is still a way to go).

The “coarseness” associated with him is more so aligned to his experiences than his writing. He had an affair with his employer’s wife, Lydia Robinson, and there are letters in which he begs friends for money for gin – so, I think there is an unseemliness associated with him, something dangerous but not necessarily in the sexy Byronic way, however justified this image may be. Part of the conference’s aim is to rethink this perception of Branwell and to help reinstate him within the Brontë family as a writer worthy of study. Researchers like Emma Butcher, alongside the bicentenary celebrations organised by the Brontë Society and Sally Wainwright’s recent BBC short film, ‘To Walk Invisible’ (2016), are doing wonderful work on these issues surrounding Branwell, so we hope the conference will contribute to these discussions.

Judging by the topics that will be presented at the conference, do you detect any general trends or significant re-evaluations of the Brontës in this bicentenary period?

The programme is incredibly diverse, so it is really exciting to see so many interpretations and reappraisals of “coarseness” emerging. We have considerations of drunkenness, queerness, incest, self-harm, bird imagery, political violence, and more. There are several considerations of Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, which is great to see, as Anne’s writing deserves more “airtime” and I think this is down to new books, like Samantha Ellis’s Take Courage (2017) and Nick Holland’s In Search of Anne Brontë (2016), taking Anne as their subject.

All the papers are challenging the “Brontë myth” in some way or, at least, the dominant narratives that still stick to the Brontës and their novels. We are hoping to emphasise and uphold the complexities and contradictions at play in their works; they do not have to be just “one thing”, like romantic-with-a-small-r writers who wandered the Yorkshire moors in isolation, totally removed from reality.

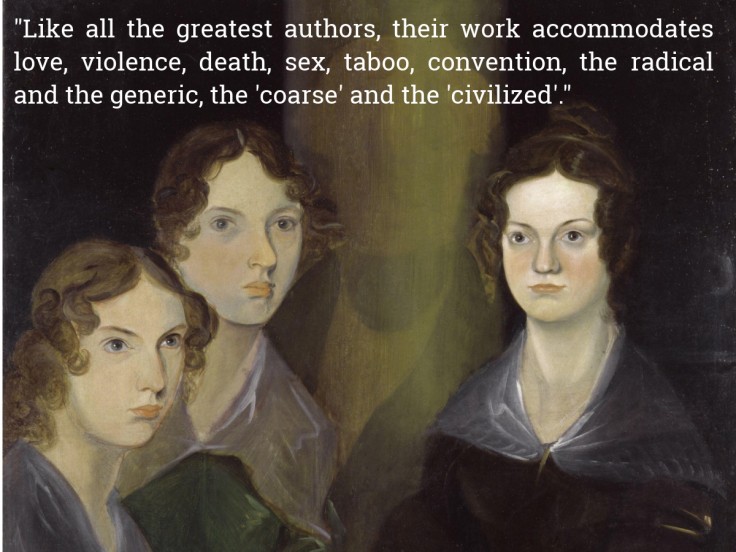

Many of the papers in the programme situate the Brontës firmly in the “real world” and all its grittiness. Like all the greatest authors, their work accommodates love, violence, death, sex, taboo, convention, the radical and the generic, the “coarse” and the “civilized”. The theme of “coarseness”, with its many definitions and interpretations, can contain all these elements, which is what we think will make this conference so dynamic and energetic. We want to ask some tough questions and generate stirring, lively discussions about the Brontës, who they were and what they mean now – if that doesn’t sound too ambitious!

You’re putting this conference together with an academic colleague from Brunel, and the Brontë Society. Given the wide interest in the Brontës, are you hoping for a range of scholars, readers and those who simply want to find out more?

Yes, absolutely – one of our aims was to encourage independent researchers and artists to offer their own takes on the topic. And we are also keen to see a range of attendees to spark wider debates and open up discussion. By collaborating with the Brontë Society, we wanted to create more of a dialogue between experts and enthusiasts both in and beyond universities. We are all Brontë “fans” in some shape or form; harnessing this shared interest can only be a positive thing, especially when working together to contribute to the family’s legacy. And working with Claire from Brunel University has been really rewarding, as we are both on the same page in terms of what we hope to see from Brontë studies moving forward.

We were also adamant about there being a strong representation from students, both speaking and in attendance. With the generous help of the British Association for Victorian Studies, we have secured three bursaries for postgraduates and undergraduates, which is a wonderful chance for us to help those on low incomes attend the conference.

We have speakers coming from all over the world, including Sweden, the U.S., and China, as well as more local speakers, including Durham’s own Dr Sarah Wootton, who will be talking about self-harm in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette. One of the best things about hosting this conference at Durham University (the venue is St Chad’s College) has been having so many of the brilliant researchers and administrators from the English department involved – everyone has been really enthusiastic and I think that will be reflected in the day itself.

Are there any other events people who can’t come to the conference should look out for this year amid the anniversary celebrations?

There is plenty happening in the next few years in the run up to Anne Brontë’s bicentenary in 2020, which will be the climax of the Brontë anniversary celebration. In November this year, the Brontë Society are hosting a symposium in Leeds dedicated entirely to Branwell Brontë’s life and work, so that will be another opportunity to reappraise his legacy. Next year, it is Emily Brontë’s turn in the spotlight, so there will be another Brontë Society conference in September 2018 held in York to celebrate. We will be providing further information about that event in our own conference packs, so I am looking forward to reading more about that soon.

We will also be publishing a selection of articles from the conference in a special issue of Brontë Studies, due out in January 2019. We would love to host other events that lead on from this conference – so, stay tuned just in case!

Registration for The Coarseness of the Brontës: A Reappraisal is open now; three bursaries are available for undergraduate and postgraduate students. Follow the conference on Twitter @coarsebrontes for the latest updates, and contact coarsebrontes@gmail.com for more information.

The Coarseness of the Brontës is a joint initiative between Durham University, Brunel University, and the Brontë Society. It is generously supported by the British Association for Victorian Studies (BAVS), and the English Studies Department and CAROD at Durham University.

What do you think? Share your thoughts below.