How T.C. Nivedita’s experience of lockdown mirrored Antoinette Cosway’s confinement in the world of Wide Sargasso Sea.

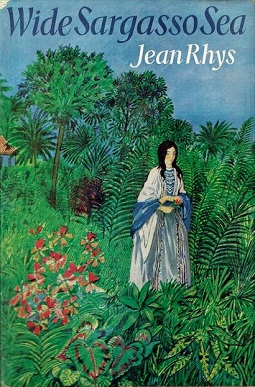

The recent year (or more) spent self-isolating and social distancing witnessed a proliferation of popular articles comparing life in COVID-19 lockdowns to the confinement and tedium of Jane Austen’s heroines. Oddly enough, spending those long days indoors, I was reminded more of the relatable plight of another literary heroine – Charlotte Bronte’s Bertha Mason and, more particularly, her reincarnation as Antoinette Cosway in Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966).

Re-reading Wide Sargasso Sea during the pandemic, in preparation for my recent Postgraduate English article, I was struck anew by its acute spatial sensibilities. Indeed, Antoinette’s life can be read as a saga of confinement, both voluntary and enforced, material and metaphorical. However, unlike the ennui of the women who populate Austen’s pages, Antoinette’s solitude is not static through time and space. As the novel travels from the Caribbean islands to meet up with Jane Eyre in England, Antoinette is shuttled from one physical embodiment of isolation to another, each altering her perception of confinement as well as her identification with space itself. From my contemporary vantage point of enforced isolation, this evolving relationship with space and spatiality gained currency. The pandemic forced me to build a personal sanctuary, and with the bustle of the twenty-first century suddenly rendered silent, my life seemed to resonate with the seclusion of a nineteenth-century woman reimagined in the twentieth.

As the novel opens, Antoinette is living with her mother in her childhood home in Coulibri Estate in what she believes to be voluntary isolation. She is used to her solitary life and has established a companionship with the materiality of the space around her. In their familiarity, the furniture, looking-glasses, cups, saucers, trees, and walls grant her comfort and security. They make her feel safe from strangers. Coulibri’s comforting insularity would be relatable to many of us since the pandemic-enforced isolation. Back home from university, I found solace in the familiarity of my surroundings – they were a refuge, offering some much needed respite. Like Antoinette attempting to escape the oppressive reality by grounding herself to Coulibri, I sought to distance myself from the unsettling, uncertain world outside by focusing on the materiality of my isolation. It was a comforting exercise until I realised that, as days passed, my isolation had turned into loneliness.

Antoinette’s awareness of the changing nature of her isolation is perhaps more gradual than mine, albeit with more far-reaching consequences. Paradoxically, she comes to this realisation once she is free of the physical insularity of Coulibri and that of the convent where she is confined later. After her marriage to an Englishman, Antoinette moves to the summer estate of Granbois, a place that holds fond memories for her. However, the presence of her husband, embodying all the dominance of the White male institution, taints the familiarity of the space. The safety and security Antoinette associated with self-imposed isolation are now replaced by fear, anxiety, and frustration as she begins to experience her seclusion as enforced confinement. Unlike Antoinette, however, my exasperation stemmed from continued physical isolation. My immediate confines were no longer able to function as a comforting enclave, and its materiality had become constricting. Much like Antoinette, I began to weigh spatial freedom against personal safety. Confronted with extended lockdowns, I began to wonder when this isolation would end. When can I go outside? When can I resume my life?

Antoinette’s confinement becomes absolute with her incarceration in the famed attic of Thornfield Hall. She, too, seeks answers to these questions, which she finds only by staging a fatal escape and burning down her prison. But those of us in the twenty-first century continued biding our time in isolation, venting our frustrations and grudgingly accepting our confines, which had now become a stifling retreat.

Eventually, lockdowns were lifted. Restrictions were eased. Life seemed to restart. Yet, there was undeniably a lingering sense of disruption in my post-pandemic experience of space. Like Antoinette, I now equated insularity with both anxiety and security. After spending the better part of two years indoors, I spent this summer travelling. The sprawling valleys of Kashmir in the foothills of the Himalayas could not have been more open and inviting, but my experience of the great outdoors was characterised by a strange ambivalence – I found it liberating, yet I desired the safety of my home where I had been cocooned for too long. I was at once Antoinette out of Coulibri and Bertha out of the attic.

So, while pastimes out of the Georgian era and unfulfilled Austen-esque yearnings from behind closed doors might have afforded us a romantic escape, the reality of the isolation experience was often much closer to Antoinette’s fiery flight.

Read T.C. Nivedita’s article A Language of Loneliness: Spatial Confinement and the Revolt of Textual Selves in Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea for free in our open access Postgraduate English journal.

Featured image credit: Back View of a Woman Walking in a Narrow Alley, via Pexels. Public domain.

What do you think? Share your thoughts below.