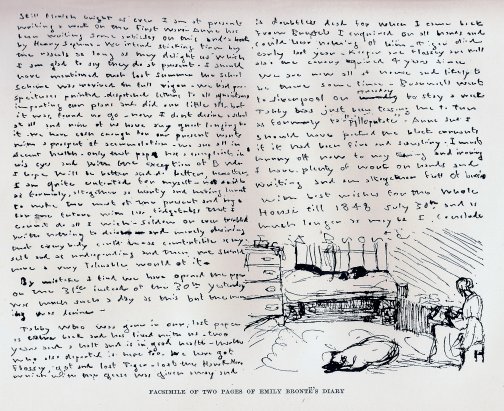

Emily Brontë was not a prolific diary-keeper, but the journals she did record give us an insight into life at Haworth parsonage. In this second of three posts exploring the diaries of Emily and Anne Brontë, Sophie Franklin turns the pages and crosses the threshold of the writer’s home and her unfathomable mind.

![Sketch by Emily Brontë showing herself and Anne at work in the dining room of the parsonage [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://readdurhamenglish.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/emily-bronte-sketch.jpg?w=242&h=300)

Emily’s sentences run on unpunctuated, so that her entries become a kind of stream of consciousness. This lack of grammar makes her sudden slip into the Gondalian world all the more surprising. In this entry, written when Emily was sixteen, her mention of Gondal and Gaaldine jolts the reader from the delightful mundanity of her pets and “pilloputate” into another realm, unseen yet just as vivid:

24 November 1834

I fed Rainbow, Diamond Snowflake Jasper pheasant (alias) this morning Branwell went down to Mr. Driver’s and brought news that Sir Robert Peel was going to be invited to stand for Leeds Anne and I have been peeling apples for Charlotte to make us an apple pudding and for Aunt nuts and apples Charlotte said she made puddings perfectly and she was of a quick but limited intellect. Taby said just now Come Anne pilloputate (i.e. pill a potato) Aunt has come into the kitchen just now and said where are your feet Anne Anne answered On the floor Aunt papa opened the parlour door and gave Branwell a letter saying here Branwell read this and show it to your Aunt and Charlotte–The Gondals are discovering the interior of Gaaldine Sally Mosley is washing in the back kitchen

There is very little personal content here; her descriptions relate either to the house and her family, or to the fictional world of her and Anne’s creation. This lack has led critics and readers to seek clues to Emily’s personality in her poetry and only novel, Wuthering Heights. Notably, this process of paralleling her fiction with her biography apes Emily’s own merging of domesticity with imagination in the journal papers. The gap between a person’s internal world and the tangible world can perhaps be bridged through the writing and reading of diaries.

As a postscript to the diary paper written on 26 June 1837 (their brother, Branwell’s birthday), Emily includes an amusing vignette of her Aunt Branwell telling her to stop writing:

I guess that this day 4 years we shall all be in this drawing-room comfortable I hope it may be so. Anne guesses we shall all be gone somewhere comfortable We hope it may be so indeed. Aunt: Come Emily it’s past 4 o’clock.

Emily: Yes, Aunt Exit Aunt

Ann: Well, do you intend to write in the evening Emily: Well, what think you (We agreed to go out 1st to make sure if we got into the humour. We may stay [in]–)

The playfulness of this scene emphasises the fact that these papers were written as part of a ‘secret game’ meant for the sisters’ eyes only. Augustin Trapenard points out that, on the MS copy, the final word after ‘We may stay’ is illegible. It could be “in”, but it could also be “out”. This indeterminacy highlights the ‘impossibility for the intrusive reader to penetrate the private sphere of the two sisters’. Even when we have access, however uninvited, to another person’s private writings, there remains a barrier of interpretation and understanding. It would seem diaries always leave us wanting more.

Emily’s last diary paper, written 31 July 1845, finally gives us an insight into how she views herself:

I am quite contented for myself–not as idle as formerly, altogether as hearty and having learnt to make the most of the present and hope for the future with less fidgetiness that I cannot do all I wish–seldom or ever troubled with nothing to do, and merely desiring that every body could be as comfortable as myself and as undesponding and then we should have a very tolerable world of it

In order to achieve contentment, Emily advocates living in the moment, keeping busy, and trying to be less “fidgety” about the future. This desire to “live in the moment” is a major strand of mindfulness, a psychological process which has become hugely popular in recent years. Emily’s diary shows, then, how little humans have changed – we still seek happiness, some kind of contentment, and struggle with staying “present”.

Her words also reveal a sympathy for others, as her main desire is for everyone to be as comfortable as she is and, therefore, for the world to be more “tolerable”. Far from being a closed-off moor-wandering sphinx, here Emily proves herself to be aware of the wider world and just as concerned with finding contentment as anyone.

Read Sophie’s other posts in this series on The Brontë diaries. You might also like to listen to this podcast celebrating the Brontës.