War and Peace hit the UK bestseller lists in 2016 in the wake of the BBC adaptation, challenging the perception that Tolstoy and his contemporaries are too wordy and dull to interest us today. Viv Groskop appeared at Durham Book Festival to confirm the relevance and rewards of Russian literature. Gareth Reeves was there to get his fix.

Caroline Beck, who chaired this event, described Viv Groskop’s book as a who’s who of Russian literature, recommending it to anyone who thinks that reading Crime and Punishment or War and Peace is like wading through treacle. Indeed, Viv really wants people to overcome their fear of these classics. Her book, The Anna Karenina Fix: Life Lessons from Russian Literature, was written on the back of a series of blogs she produced for The Guardian, about the excellent BBC adaptation of War and Peace – or, as Caroline described it, ‘Phwoar and Peace’, alluding to James Norton as Prince Andrei. Based on user comments, Viv realised that there was a dedicated fan base for Russian literature in Britain and, given her expertise as a talented linguist and professed Russophile, she decided to write the book.

Her fondness for Russian literature began in Bruton, Somerset, where she grew up. Bruton in the 1970s was largely middle class and a ‘monocultural place’, and Viv felt slightly out of place due to her surname. “Where did it come from?” she wondered. At the tender age of five, she asked her parents about it, and they told her that it was a very British name. Yet, Viv thought, here I am surrounded by Smiths and Sticklands. Later, in her early teens and quite by chance, she came across a copy of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina in a second-hand book shop. Although her parents were readers, they tended to read books by Frederick Forsyth or Catherine Cookson rather than the classics, so it was a particularly special find. And it proved to be a revelation for Viv because here were characters with ‘unusual’ names like hers. “I must be Russian!” she thought.

Her fondness for Russian literature began in Bruton, Somerset, where she grew up. Bruton in the 1970s was largely middle class and a ‘monocultural place’, and Viv felt slightly out of place due to her surname. “Where did it come from?” she wondered. At the tender age of five, she asked her parents about it, and they told her that it was a very British name. Yet, Viv thought, here I am surrounded by Smiths and Sticklands. Later, in her early teens and quite by chance, she came across a copy of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina in a second-hand book shop. Although her parents were readers, they tended to read books by Frederick Forsyth or Catherine Cookson rather than the classics, so it was a particularly special find. And it proved to be a revelation for Viv because here were characters with ‘unusual’ names like hers. “I must be Russian!” she thought.

The complexity of the names in Russian novels are one of its initial difficulties, but Viv advised us to ignore it. Yes, there are variations – ‘Anna, Anya, Anyushka, and so forth’ – but there are almost as many in English – ‘Peter, Pete, Peterkin, the Pete-ster’ (!). In other words, we have similar patterns in our language, so why worry! Viv said that people had been led to believe in the difficulty of Russian books, but this is largely a myth, and in fact we could draw useful lessons from these books if we’d only pick up and read them.

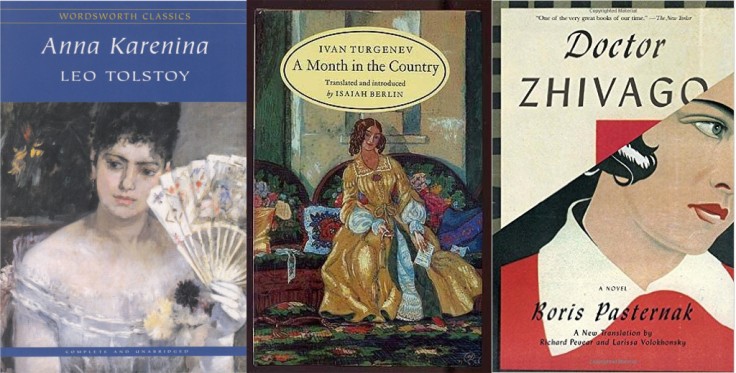

Anna Karenina, which is ‘warm and beautiful’ but also ‘ghoulish and depressing’, tells us to be true to ourselves. Viv noted that Tolstoy’s society would not permit a married woman to have an affair, and so she has to die at the end of the book. However, Viv more readily identifies Tolstoy – passionate and hot-headed as he was – with Anna than with Levin, the young, rather dull man who is very much into his agriculture and has traditionally been seen as Tolstoy’s surrogate.

Viv then proceeded to share three stories from her life, tragic and comic, and showed how they relate to Russian literature.

Turgenev and skinny dipping

One of Viv’s first visits to Russia involved falling in love with a guy who did not feel the same way about her. He drank to excess and suffered from mange but, she assured us, was beautiful. One night, on a beach, Viv took her clothes off and asked him to go skinny-dipping with her: to which he responded, ‘Why are you taking your clothes off?’ She swam into the sea, looked back and found him running off with her clothes and shouting ‘The English woman has gone crazy!’ This was, she told us, her first and last skinny dip. She learnt from Turgenev’s play, A Month in the Country, on the theme of unrequited love, that it is best to ‘walk away’ from such relationships. If only she had read it sooner…

Pasternak and death

Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago opens with a powerful description of a funeral. When Viv was teaching English in Russia, one of her friends tragically hanged herself at the age of 19. Viv was invited to the funeral but told to bring her makeup with her. She was first taken to the morgue, which she described as a ‘Dostoyevskyian scene’. This was the first time she had seen a dead body. The reason for bringing her makeup, which was apparently hard to come by in early-1990s Russia, was to dress the corpse for the funeral. The whole thing was ‘incredibly surreal’, and it made Viv realise that there are some cultural gaps that cannot be crossed.

Anna Akhmatova

In her time spent in Russia, Viv made many friends interested in literature. Akhmatova, an extraordinary twentieth-century poet, was revered in the same way that the great male Russian writers were. One of her friends, Tanya, who nursed her back to health from dysentery (‘probably the subject of my next book’), was part of an Akhmatova appreciation society, which involved dressing up in black and reciting the poetry to a small, dedicated group of admirers. Viv recalls trying to recite the poetry in a manner, she later realised, would have resembled the French of ‘Allo ‘Allo rather than the precise and trance-like recitations her friends mustered. But Akhmatova was a heroic person as well as a great poet – defiant towards Stalin and his grisly gang, a strong individual who refused to leave her country despite hideous pressure – several close family members were sent to Gulag camps. The lesson here is a powerful one of sticking to one’s principles, although we could hardly expect to match Akhmatova in the degree of her convictions.

Caroline asked whether there was still reverence for the Russian classics among today’s Russian youth. Viv believed that there would be a resurgence, or it would certainly be interesting to see if there was. Vladimir Putin is currently trying to instil national pride by looking back to the Tsars, in particular the Romanovs, and in a sense doing to Stalin what Stalin tried to do to so many others by wiping Stalinism out of history. The 2005 TV adaptation of Bulgakov’s great, though hardly subtle, satire The Master and Margarita garnered 70 million viewers, which suggests that satire is alive and well, although, according to Viv, national pride may prevent current comics and satirists from criticising Putin.

But what about Viv’s surname? (A useful question from the audience.) Was she indeed of Russian ancestry? Actually, no! She discovered, after a small lifetime of Russophilia, that she was in fact of Polish ancestry – or, as she brilliantly put it, ‘wrong country, wrong language, wrong books, and sleeping with the enemy!’

All in all, the atmosphere at this Town Hall event was warm and convivial, upbeat and fun, and refreshingly free of academic fustiness. Although the life lessons that Viv drew from the Russian masters felt trite – do we really need to read Anna Karenina to learn to be true to ourselves? – it was conveyed in such a personal and charming way that it didn’t matter. My only serious regret was that, unlike the average book by Tolstoy or Dostoyevsky, it was all over too soon.

Russian literature is not the only source of inspiration for modern living. In his earlier post, Gareth Reeves shared four other books that have helped him through challenging times. What books have affected your life?

Hello. Thanks for your post. I really love the way you write. I am an constant reader of this site and also a bookaholic. In this moment i read http://justreadbook.com/book/437474280/anna-karenina-vintage-classic-russians-series but i love every genre. I wish everyone to read it. From drama to comedy i like to read everything i can. Books are a great way to spend your time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks George. Lovely to meet a fellow bookaholic. Books certainly can consume a lot of time, but they never waste it.

LikeLike

Married women of the upper classes could have affairs in Tolstoy’s society as long as they were discreet and didn’t annoy their husbands. Anna’s mistake was to actually display her romance in public.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved your review! I will definitely read this book because I am a big fan of Russian literature.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment Lisa. Really hope you enjoy Viv Groskop’s excellent (and funny) work.

LikeLike